The Agentic CFO: In The Arena CFOs Design The Future, Tame Free Cash Flow And Maximize Enterprise Value

Stop measuring the past, and start designing the future with AI and agents

Arrrrr! 🏴☠️ Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of Category Pirates. Each week, we share radically different ideas to help you design new and different categories. For more: Audiobooks | Category design podcast | Books | Sign up for a Founding subscription to ask the Pirate Eddie Bot your category design questions.

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and Category Pirate,

Jeff Klimkowski didn’t plan on his career ending up in the toilet.

For more than a decade, he built a career in the high-stakes world of investment banking. He loved the work, the rigor, the precision, and the people. He learned how capital moves, how deals get done, and how to be a trusted advisor to CEOs.

At the same time he and a few childhood friends saw the future after having too many burritos and beer. Flushable wipes for men.

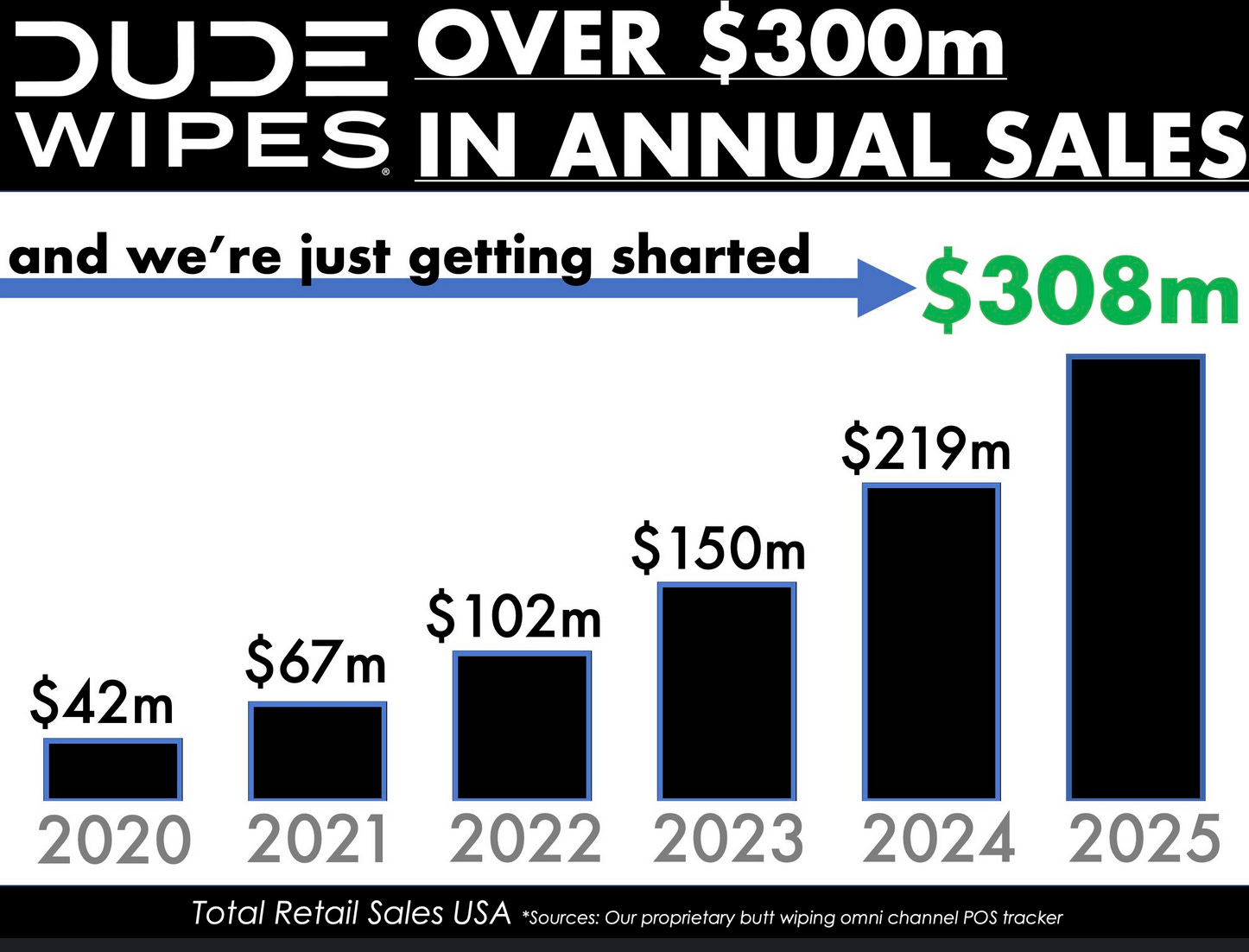

They called it DUDE Wipes.

What began as a side hustle with a sense of humor became something serious. And Jeff, the banker who once modeled billion-dollar companies in spreadsheets, decided to help build one from scratch.

He got up out of the stands and got into the arena.

But Jeff didn’t just become CFO. He re-designed the CFO role.

Most of the companies he dealt with as an i-banker were large, mature companies.

DUDE Wipes was a high-growth startup. Creating a new category was not in his Deutsche Bank training manual. He wasn’t just doing spreadsheet kung fu. He was wrestling down invoices. Planning for future growth and putting in the framework for scaling a massive brand.

He was determined not to dilute their equity and made sure the only outside capital was the original check from Mark Cuban (on Shark Tank), until they hit escape velocity. He wasn’t just CFO. He was also the primary seed investor and line of credit for DUDE Wipes using his i-banking bonuses to bankroll working capital.

He wasn’t an ivory tower CFO, but an in the arena CFO. With big-time entrepreneurial skin in the game. He went to customer meetings with Walmart so he could look at the whites of the buyer's eyes before he spent precious working capital on inventory. He met with his co-manufacturers to make sure supply and demand were aligned.

Jeff trained himself to be crazy about cash flow.

Because early on, DUDE Wipes cash flow and Jeff’s cash flow were one and the same.

At DUDE Wipes, he helped design the rhythm between cash and creativity, supply and storytelling, and data and demand. The systems he once used to evaluate companies became the systems he used to build one from the ground up.

Then, DUDE Wipes hit its first of many supply-chain constraints.

The perfect storm of rising demand, retail expansion, and a thin cash position forced a moment every CFO knows too well: the numbers were “right,” and the business was tight. The Dudes needed to change. Every move the traditional finance playbook recommended (slow down POs, tighten spend, delay production) would have destroyed the momentum DUDE Wipes needed to survive.

Once the category sees it, they can’t unsee it. That new demand has to go somewhere. Had the Dudes failed to scale, they would have designed a category for someone else to dominate. And they knew it.

The legacy CFO model (close the books, manage cash, control the budget, protect the quarter) was useless for high-growth, consumer product category-creation. The category moved faster than the Dudes thought possible. And Jeff realized finance couldn’t be backward-looking anymore.

So, he focused on a different category of finance for category creators. Finance who think it’s their job to power the company to create a new category, not just hit their target.

Jeff built real-time visibility, tore out processes that slowed the team, and created a rhythm between free cash flow and creativity that kept DUDE Wipes alive and growing.

Jeff represents the future of finance leaders—the Agentic Chief Financial Officer.

This mini-book is about the shift from measuring financial performance to multiplying financial potential. In the post AI world.

You’ll see how Jeff’s ability to reject the premise has grown DUDE Wipes into a $300M+ company.

Because an Agentic CFO doesn’t just run the numbers. They orchestrate outcomes and turn finance from a rear-view function into the operating system for speed.

You’ll also see:

Why the old CFO model is collapsing, and the reason legacy finance functions slow companies down.

The new mental model of the Agentic CFO, and why free cash flow (not EBITDA) is the strategic metric of belief.

How to use AI agents to build financial intelligence and turn timing, demand, and cash flow into a self-reinforcing system of growth.

Whether you’re a finance nerd or you just want to understand how Category Kings approach a P&L, this mini-book will help you consider a different lens and mindset for finance.

So grab your ledger. We’re going on an adventure.

Why Finance Has A Category Problem

For decades, the CFO was trained to master the past.

The job was about precision—closing the books, reducing variance, and forecasting next quarter’s numbers with absolute certainty. It was a noble pursuit, built on the belief that control equals certainty. But that discipline hardened into dogma.

Finance became the department of no.

A world of careful gatekeepers guarding budgets instead of guiding growth.

Inside too many companies today, the financial system still runs on an inherited logic from the industrial era. The goal is predictability and risk mitigation, and the reward is consistency. CFOs are told to “protect shareholder value,” which often means keeping everyone else from making bold moves that might screw up the quarterly earnings report.

You can’t create a different future if your lens is to protect the status quo.

What began as a system for enabling growth became a system for containing it.

The traditional finance mindset was built for an economy of factories, not digital feedback loops.

It valued control because control was scarce. The CFO was the keeper of truth. The one person in the room who knew where every dollar went. That authority came with power, but it also created isolation.

As companies scaled, their financial systems scaled with them.

ERP platforms got bigger, and reporting cycles got longer

Forecasting became a quarterly theatre of variance explanations and budget revisions

Somewhere along the way, the discipline of finance started to focus on compliance

When compliance becomes the culture, curiosity disappears.

Now don’t get us wrong. We’re very big fans of legendary governance. And controls are an important part of the job, but they are in service of producing legendary outcomes.

Most CFOs didn’t choose this system. Universities, consulting firms, and Wall Street all rewarded prudence, perfection, and predictability. Finance became fluent in accounting but lost its imagination.

A rigid mindset is dangerous when markets move faster than spreadsheets.

While startups run real-time AI-powered simulations, many large organizations are still waiting for last quarter’s reports to be finalized. Their data lives in silos. Their teams operate in sequence, not in sync.

By the time a financial insight arrives, the opportunity has already passed.

This is a category problem.

Finance has been defined by what it measures, not what it makes possible. It has been positioned as a back-office function instead of a front-line capability. And like any category that stays frozen too long, the world moves on without it.

The world doesn’t need more cost controllers.

It needs Creators.

The problem is the identity that the old system creates.

Traditionally, CFOs have been trained to slow the business down.

The safest decision was always to say “no.”

The least risky move was always to wait and see.

The highest praise came from preventing something, not creating something.

Finance is the only function in a company where doing nothing is considered a win.

Marketing wants growth. Sales wants acceleration. Product wants innovation. Ops wants efficiency.

But finance wants the world to hold still long enough to reconcile it.

CFOs became guardians of the reporting cycle, instead of designers of the business cycle. They could do everything “right” according to the old playbook and still suffocate the company they were hired to protect.

This is the premise you must reject.

Because when a category demands speed, and your identity demands caution, you are structurally incapable of leading the company where it needs to go.

Which brings us to the future.

Milton Friedman’s Four Ways to Spend Money

In 1975, University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman laid out one of the most elegant frameworks for understanding spending behavior. He identified four ways to spend money:

Your money on yourself: Most careful about cost AND value.

Your money on someone else: Careful about cost, less careful about value.

Someone else’s money on yourself: Careful about value, less careful about cost

Someone else’s money on someone else: Not careful about cost OR value.

#1 is like when you buy your first house. #2 is a gift for someone. #3 is an expense account lunch. #4 is the government, with no care for cost or value.

That’s why the Pentagon has failed seven consecutive audits.

That’s why they can only account for 39% of their $3.8 trillion in assets. That’s why Donald Rumsfeld stood at a podium on September 10, 2001, and admitted the Defense Department “cannot track $2.3 trillion in transactions.”

Bernie Sanders called the Pentagon “the only agency that has never passed an independent audit.” Chuck Grassley complained about “$14,000 toilet seats” and “warehouses full of spare parts they’ve lost track of.”

Left and right agree: when nobody owns the money, and nobody owns the outcome, waste isn’t a bug. It’s the system working as designed.

Friedman’s insight was ruthlessly simple and can also be used to explain different CFOs!

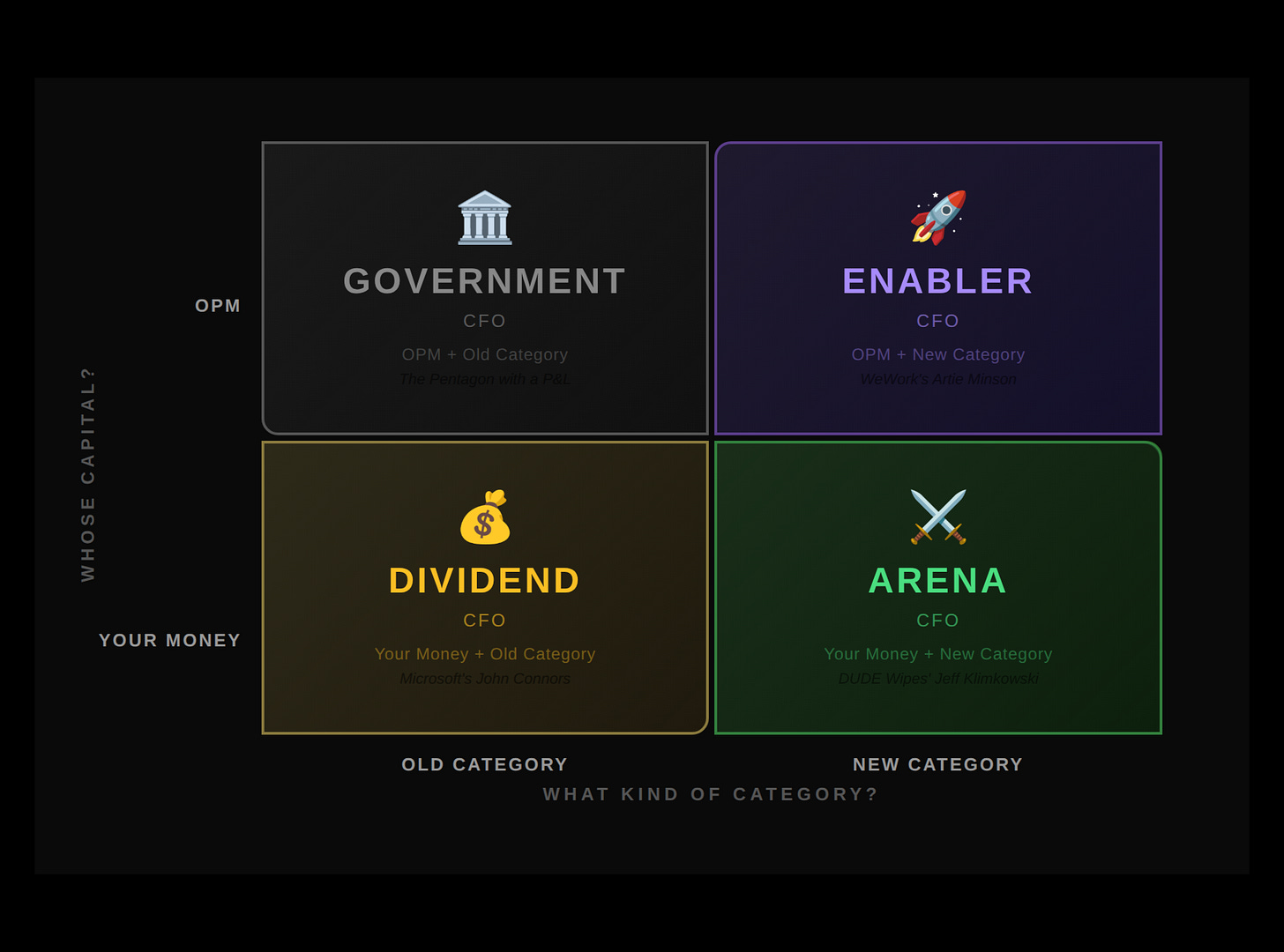

We adapted Friedman’s framework to how CFOs actually behave—based on two variables:

Whose capital are they deploying? (Their own money or OPM—Other People’s Money)

What kind of category are they operating in? (A new category they’re creating with no competition, or an old category they are competing in)

Plot those two variables, and you get four distinct CFO archetypes:

Your Money + New Category = ARENA CFO

Your Money + Old Category = DIVIDEND CFO

OPM + New Category = ENABLER CFO

OPM + Old Category = GOVERNMENT CFO

Each quadrant produces a radically different relationship with cash, risk, and accountability.

The Arena CFO (Your Money + New Category)

This is Jeff Klimkowski.

His cash and DUDE’s cash were the same thing. That forces precision—you can’t be reckless because it’s your money, and you can’t be timid because the category is moving faster than your spreadsheets.

Friedman would recognize this as the most careful spending of all. The Arena CFO obsesses over both cost AND value because failure means personal loss, and hesitation means someone else defines the category.

Jeff has a goal of Zero Free Cash Flow at year's end.

What? Don’t you want more Free Cash Flow? You don’t want to be like Jeff Bezos and be negative Free Cash Flow and land-grab like crazy?

Not Jeff.

He wants DUDE Wipes to be perfectly calibrated at year's end. Not too conservative to the point of not investing enough to grow the category. He knew that if DUDE Wipes didn’t invest, the legacy category would persist and toilet paper would continue to cause Itchy Butt Syndrome for billions of anuses in the world.

But if he invested too far over their skis, they would need to raise money and dilute their equity. He was calibrating capital to reality in real time—because he couldn’t afford to do anything else.

Zero FCF is the financial equivalent of a surfer sitting in the pocket of a wave.

The Arena CFO doesn’t sit in the skybox watching the game. They’re on the field, their body on the line with every play.

The Dividend CFO (Your Money + Old Category)

In 2004, Microsoft’s CFO John Connors did something Wall Street hadn’t seen in decades: he announced a $75 billion capital return to shareholders—a one-time special dividend of $32 billion plus ongoing buybacks and dividends.

Why?

Because Connors recognized a hard truth: Microsoft had won its category. The PC operating system war was over. And a CFO sitting on a mountain of cash in a mature category has two honest choices: return it to shareholders, or admit you’re just bad at deploying capital.

Connors chose to return it. “Our shareholders can invest this better than we can,” was the implicit message.

By the way, when companies buy back their stock, they are also saying, “we’ve run out of ideas.”

This is the Dividend CFO. They are careful about cost as it’s still their shareholders’ money, but focused on returning cash because the category no longer demands aggressive reinvestment. Friedman would call this the “birthday gift” quadrant—you’re still watching the price tag, but you don’t invest because you don’t see any upside.

The Dividend CFO isn’t a failure. They’re realists. When the category is mature, the highest-conviction bet is to stop pretending you have high-conviction bets.

The Enabler CFO (OPM + New Category)

This is the WeWork playbook.

Artie Minson served as CFO during WeWork’s hypergrowth phase—the era when SoftBank’s Vision Fund was pouring billions into the company at valuations that defied gravity. Minson’s job wasn’t to create cash flow. It was to enable Adam Neumann’s vision.

When you’re spending other people’s money in a new category, the incentives bend toward optimism. The capital feels infinite. The category feels inevitable. Your job becomes processing spend, not questioning it.

Friedman would recognize this as the “expense-account lunch” quadrant. You care about value (you want the vision to succeed), but you stop caring about cost because the bill isn’t yours.

Minson wasn’t incompetent. He was operating exactly as the incentives predicted. When you have no skin in the game but believe in the destination, you become an enabler—processing capital toward a future that may or may not materialize.

WeWork burned through over $13 billion before reality intervened.

The Enabler CFO is seductive. They sound like visionaries. But without ownership, vision becomes vapor.

The Government CFO (OPM + Old Category)

This is the Pentagon with a P&L.

The Government CFO operates in the most dangerous quadrant: spending other people’s money in a category someone else defined. They have no ownership stake in the outcome, and no urgency to redefine the game. The result?

Process over purpose.

When GM took $50 billion in taxpayer bailout money in 2008, critics called it “Government Motors.” But here’s the truth: GM was operating like the government long before the bailout.

From 2020 to 2023, GM ran Super Bowl ads four years in a row—at $7 million per 30-second spot, running 60-90 second executions with A-list celebrities. Will Ferrell. Dr. Evil. Netflix partnerships.

The message? GM is serious about electric vehicles.

The reality? In 2022, GM sold just 39,096 EVs—less than 2% of their total volume. Most of the cars in those Super Bowl ads didn’t exist. A 2023 Newsweek headline captured it perfectly: “GM Makes Great Electric Car Ads, but Where Are the Cars?”

Meanwhile, Tesla spent $0 on advertising and dominated the EV category.

This is the Government CFO in action. Spending $3.25 billion annually on advertising. Knowing the trade promotion math doesn’t work. Knowing 35-40% of every CPG marketing dollar is wasted. But continuing anyway because... “we did it last year.”

Nobody gets fired for maintaining the status quo. Nobody gets promoted for questioning the orthodoxy. The safest move is always to process the budget, hit the benchmarks, and let someone else deal with the consequences.

The Government CFO isn’t evil. They’re just playing the game the incentives created.

The Question Every CFO Must Answer

Which quadrant are you in?

Not which quadrant you think you’re in. Not which quadrant your title suggests. Which quadrant do your actual incentives create?

Because here’s Friedman’s uncomfortable truth: you will behave according to your incentives, regardless of your intentions.

If you’re spending OPM in an old category, you will drift toward process. You will optimize for benchmarks instead of breakthroughs. You will protect the quarter instead of creating the future.

The only way to escape the Government CFO quadrant is to change the incentives:

Create ownership. Tie your compensation to outcomes that matter, not activities that check boxes.

Create urgency. Redefine the category or get redefined by it. The status quo is a trap, not a strategy.

Create accountability. Build systems where cash flow tells the truth faster than anyone can hide it.

The Arena CFO doesn’t exist because Jeff Klimkowski has superior willpower. The Arena CFO exists because Jeff built a system where his capital and his category forced precision.

That’s the system the Agentic CFO designs.

The Agentic CFO: The Category Designer Of Free Cash Flow and Agency

Across industries, a new generation of financial leaders is emerging.

They still care about discipline, precision, and accuracy. But they’re also learning to work with a new kind of teammate—AI agents that extend their reach, speed, and intelligence.

Soon CFOs will manage more agents than people.

When AI can handle reconciliations, forecasts, and variance reports in real time, the CFO’s role expands. Finance becomes less about closing the books and more about opening possibilities. It becomes the company’s connection between data, decision, and direction.

Great CFOs don’t just close the books, they create maximum agency through finance. They remove barriers that slow free cash flow. They match supply and demand with more precision. They ensure the company is default alive, needs the least amount of outside capital possible, so the company can control its own destiny.

The Agentic CFO sits at the center of that shift.

They turn numbers into signal.

They orchestrate outcomes instead of transactions.

They lead teams of human and digital agents to maximize cash flow control and enterprise agency.

They help the company move with clarity. Decisions that once took weeks now unfold in hours. AI compresses time, which means the future belongs to leaders who can see change early and act with clarity.

Does that mean all the legacy financial tools are worthless?

No.

But one of them is actively misleading.

Agentic CFOs focus on free cash flow, instead of EBITDA.

EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) is a lie.

EBITDA is what Charlie Munger called, “Bullsh*t earnings.”

It makes bankers and board members feel safe because it smooths over the messiness of reality. It seems like a predictable metric. But that’s the problem.

EBITDA hides operational rot.

It rewards bad working-capital habits.

It can make a company look profitable while it quietly bleeds out.

If EBITDA is the story you tell Wall Street, free cash flow is the story you tell yourself. That’s why legacy CFOs optimize for EBITDA and the reporting cycle. But Agentic CFOs optimize for free cash flow and the reality of the business.

Free cash flow tells the truth about your business.

It shows whether demand is real. It exposes whether growth is healthy or painful. And it shows whether the business is building momentum or burning through cash.

Free Cash Flow is basically three components:

Working capital. This is the baseline, day to day cash required to

Make stuff you can sell (e.g., inventory)

Pay people to help you sell it (accounts payable)

Collect cash from your customers (accounts receivable).

CAPEX (Capital Expenditures). These are bigger investments needed to fuel the future

For Analog/Physical businesses, this is manufacturing lines, warehouses, IT, etc.

For Digital businesses, this is software development costs, R&D, etc.

This can also be acquisitions of other companies you buy

Operating Cash Flow. This is the net cash your business generates from selling stuff

EBITDA says, “We’re doing fine.”

Free cash flow says, “Prove it.”

To understand why Agentic CFOs care about cash flow above all else, let’s look at three companies with amazing free cash flow.