Marketing As A Profit Center Part 1: How Tesla Is Using The Rental Car Category As Profit Positive Marketing

Tesla’s new form of marketing drives the core & makes money in it of itself.

Arrrrr! 🏴☠️ Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of Category Pirates. Each week, we share radically different ideas to help you design new and different categories. For more: Audiobooks | Category design podcast | Books | Sign up for a Founding subscription to ask the Pirate Eddie Bot your category design questions.

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and Category Pirate

Few people tell the CFO how to do accounting. Or the head of R&D how to do research.

But everyone tells the CMO how to do marketing.

So the CMO gets buried in “help.”

Sales reps whine: “Why isn’t our marketing sexier?”

Finance mutters: “Marketing sucks…where’s the ROI?”

Product managers say: “Just talk about the features more.”

Other executives sh*t on marketing because marketers let them. Marketing bought the lie that “You can’t tie marketing to revenue.” Or “It’s too hard to measure.” Or our favorite, “It’s more art than science.”

And that’s how marketing got stuck eating chicken nuggets while the adults talked money.

It’s time to flip the damn table.

Not with promises. Not with positioning decks. With revenue that shows up uninvited.

Because the only way to reject the premise is to show them the money.

Marketing has to stop behaving like a cost center. It has to become a predictable and powerful profit center.

In the cost-center mindset, marketing is something you pay for. It exists to create awareness, generate leads, and “build the brand.” What it is not expected to do—ever—is make money directly.

The underlying assumption is simple:

Demand already exists.

If demand is already out there, then marketing’s job is to chase it, interrupt it, or outbid someone else for it. That assumption quietly dictates everything that follows:

Google becomes a toll booth

Meta becomes a tax

CPMs become “just the cost of doing business”

This is why most marketing plans, no matter how modern they sound, collapse into the same basic equation: spend money and hope revenue happens. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t.

And in most organizations, no one can really explain why.

Cost-center marketing shows up in many forms.

Startups burn half their venture capital on paid acquisition because they need “traction.”

Large companies pour millions into campaigns with fuzzy ROI because “brand matters.”

CMOs defend dashboards full of clicks, impressions, and MQLs that never quite reconcile to revenue.

Super Bowl ads win awards and lose the plot.

Everyone is busy. Everyone is “doing marketing.” But no one can point to a clean profit line.

When revenue shows up, sales gets the credit. When it doesn’t, marketing gets the blame. That’s why marketing, in this model, is always on trial. Budgets are the first thing cut, and ROI is questioned the loudest. Over time, marketing unintentionally trains the rest of the organization not to trust it.

The trap is that cost-center marketing feels responsible.

You can spreadsheet it. You can forecast it. You can cap it.

Finance understands it because it behaves like every other expense:

Spend more → get more exposure

Spend less → get less exposure

The relationship is linear, predictable, and safe.

But that safety is the problem.

Linear spend produces linear outcomes. Linear outcomes do not produce category leaders. They produce companies stuck competing for the same pool of existing demand, year after year, with diminishing returns.

The real cost of cost-center marketing isn’t just money. It’s the erosion of trust between marketing and finance. It’s the loss of credibility at the executive table. And most dangerously, it’s the loss of imagination—the ability to believe that demand can be created, not just captured.

Cost-center marketing optimizes inside the system it inherits. It rarely questions whether that system still makes sense.

Once you see this, the core question changes.

It stops being, “How much should we spend on marketing this year?” and becomes something far more uncomfortable: what would marketing look like if it were required to make money?

Not indirectly. Not eventually. Not by association. Directly. Predictably. On purpose.

The cost-center model isn’t just outdated. It’s becoming non-viable. The world it was designed for no longer exists. Attention is saturated. Channels are auction-based. Algorithms tax every interaction. And every dollar spent at the bottom of the value ladder compounds against you.

In the old world, you could afford inefficiency.

In the new world, inefficiency is fatal.

How can marketing become a profit center?

By using one of the most important business frameworks ever.

To understand why marketing keeps getting treated like a cost—why budgets get cut first, why ROI debates go nowhere, why “brand” feels squishy while revenue feels real—you need to see the ladder everyone is actually standing on.

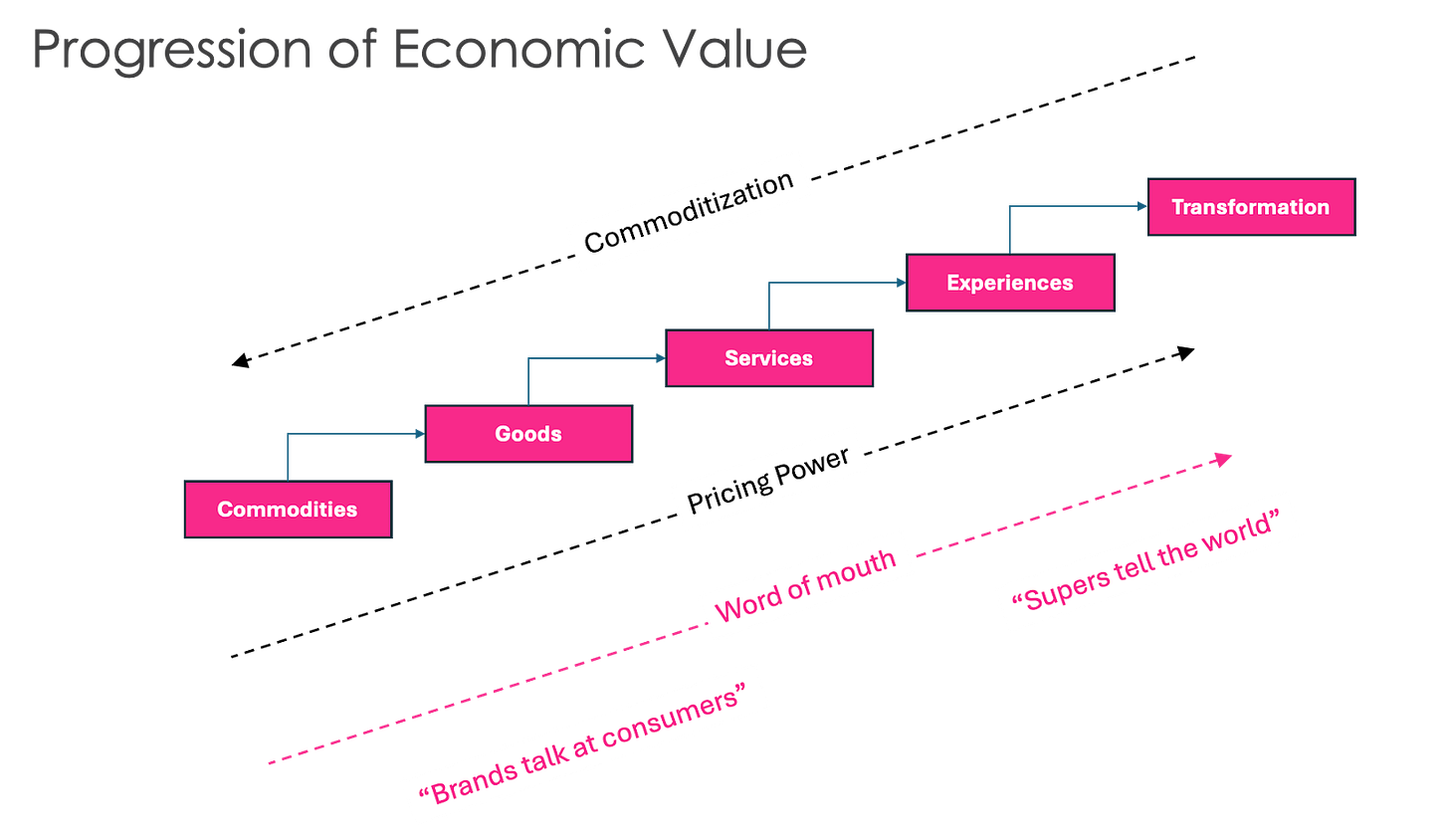

This is the Progression of Economic Value.

(We owe a massive debt of gratitude to Joe Pine and James Gilmore for this one. A great framework does three things. First, it explains the past. Second, it predicts the future. Finally, it gives you clarity and courage for what to do next. And this one does all three.)

Every business activity—marketing included—eventually lands somewhere on this ladder. And where it lands determines three things that matter more than any tactic:

How easily it gets commoditized.

How much pricing power it has.

And whether it’s treated as a cost to control or a profit engine to protect.

Most marketing today operates in the lower rungs of this ladder.

At the bottom, you have commodities: cheap impressions bought in bulk. CPMs measured in pennies. Interchangeable attention.

Move up a step and you get goods: ads, assets, campaigns, content units. Slightly more differentiated, but still linear. Spend more, get more. Stop spending, it disappears.

Climb another rung, and you reach services: performance marketing, agencies, attribution dashboards, conversion optimization. More sophisticated, more data-driven, more defensible—yet still bound by gravity. Costs scale. Value doesn’t.

This is the world most marketers are stuck in.

And from the CFO’s point of view, they’re not wrong to see marketing as a cost center here. At this altitude, marketing behaves like an expense. It requires constant input. It resets every quarter. And it gets more expensive as competition intensifies.

This is why even “successful” marketing feels fragile.

For a long time, companies could survive here.

Attention was cheaper. Competition was lighter. Inefficiency was forgivable.

That world is gone.

Today, everything at the bottom of the ladder is being automated, auctioned, or commoditized. Algorithms tax every interaction. Platforms extract more value than they return. And the more you spend chasing demand, the more dependent you become on the systems selling it back to you.

This is why cost-center marketing doesn’t just stall—it bleeds.

Move higher up the ladder, and the economics flip.

Experiences are the first updraft. Marketing stops interrupting people and starts doing something they actually want to engage with. When done well, experiences break even—or even make money—while creating disproportionate word of mouth.

Then come transformations.

This is marketing that doesn’t just inform or persuade, but changes the customer. They leave more capable, more confident, more educated, or more empowered than before. At this level, marketing is no longer a message.

It’s value.

And value can be priced.

At these altitudes:

Marketing generates revenue

Word of mouth becomes structural

Demand is created, not chased

And marketing earns its place on the P&L

This is the only place where marketing can reliably become a profit center.

This is why the cost-center mindset is becoming existential.

Not because it’s stupid (even though it is…now).

Because it’s right for a world that no longer exists.

Does anyone remember Gateway Computers?

In the late 1990s, Gateway was everywhere. Cow-spotted boxes. Big-box retail. A household name. At its peak in November 1999, Gateway’s valuation hit $27 billion.

But Gateway lived on a single rung of the ladder: goods.

Over the next decade, those goods were relentlessly commoditized. Faster processors, cheaper components, thinner margins. Laptops and desktops became interchangeable. The value leaked out of the category.

In 2007, Gateway was acquired by Acer, a Taiwanese electronics giant, for $0.7 billion.

Meanwhile, something very different happened across the aisle.

2007 is the same year Apple Computers changed its corporate name to just Apple.

Why?

Because Apple had just launched the iPhone.

Until then, Apple’s core business was also goods: laptops and desktops. And Apple knew exactly where that path led—straight into commoditization. Faster chips. Thinner laptops. Incremental upgrades. Margin pressure.

So Apple didn’t try to make better goods. They climbed the Economic Value ladder. The iPhone wasn’t just a phone. It wasn’t just a computer. It wasn’t just a music player.

As Steve Jobs said on stage:

“It’s the internet in your pocket for the first time ever.”

“An iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator… these are NOT three separate devices. And we are calling it iPhone.”

Apple moved from goods to transformation.

Not by product positioning but by category elevation.

The iPhone was thousands of times more powerful than the technology that sent humans to the moon—but more importantly, it changed how people lived. How they navigated. How they worked. How they connected. How they remembered things. How they made decisions.

That’s why when you lose your smartphone, it doesn’t feel like you lost a gadget.

It feels like you lost a limb.

This is exactly what the Progression of Economic Value predicts.

Goods get commoditized.

Transformations create pricing power.

Gateway stayed on the goods rung and watched value drain out of the category.

Apple climbed the ladder—and captured the value that followed.

That’s why transformations like the iPhone don’t just command massive pricing power.

They also generate something even more powerful.

Word of mouth marketing.

At the bottom of the ladder, marketing has no leverage.

Marketing a good or a service means a brand talking at consumers. Consumers don’t trust brands. Busy consumers tune this kind of marketing out. At best, they ignore it. At worst, they find it annoying.

So marketing compensates with volume:

More ads.

More spend.

More noise.

Which is exactly why it behaves like a cost center.

But if you have an experience of transformation, the dynamic flips. Consumers don’t trust brands—but they do trust other consumers. Especially consumers who got a real outcome.

That’s when marketing stops being broadcast and becomes word of mouth.

Supers tell other Supers.

Brands do very little work, but get massive benefits.

When Pirate Clint Carnell launched the HydraFacial brand, only a fraction of the social media posts came from the company. The vast majority came from delighted consumers talking about their glow.

And from estheticians who went from five-figure incomes to six figures because HydraFacial changed their business.

The company didn’t “push a message.” It created outcomes worth talking about.

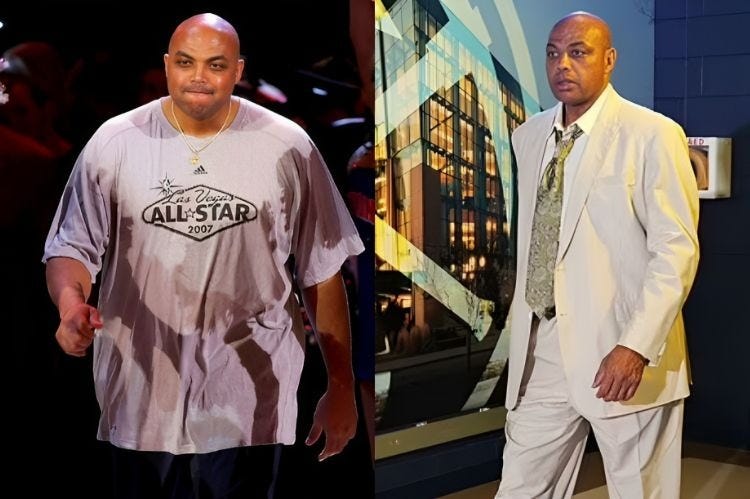

When Charles Barkley lost 65 pounds using GLP-1, he told the world about it. Other people asked him about it. The story spread. Word of mouth occurred organically and spread exponentially.

Word of mouth is, was, and will always be the greatest form of marketing.

This is why Apple’s success can’t be explained by hardware alone.

Demand followed the product in a way competitors couldn’t replicate because of the transformation it delivered.

And this is the level marketing must operate at if it wants to stop being treated like a cost—and start behaving like a profit center.

At the bottom of the ladder, marketing shouts. In the middle, marketing persuades. At the top, marketing barely speaks at all.

At this point, a reasonable pirate is probably thinking something like this: Isn’t this just a product problem?

Didn’t Apple win because the iPhone was better?

And didn’t Gateway lose because their products were worse?

That reaction makes sense. It’s also where most smart pirates get stuck.

Because on the surface, the Apple story does look like a product story. One company innovated. The other didn’t. End of discussion. But that conclusion only holds if you assume that product quality alone determines outcomes.

We’ve been trained to look at the world through the wrong lens.

If this were only a product problem, the world would be far more predictable than it is.

Companies with the best technology would always win. Better specs would guarantee category leadership. Innovation labs would reliably produce category kings.

Marketing would always be downstream, responsible only for telling the world what product already decided.

That is not the world we live in.

History is full of products that were technically superior and still failed. Phones that were more powerful than the iPhone. Software that was more capable than the category leader. Cameras that outperformed Instagram.

These products didn’t die because they lacked capability. They died because capability alone does not determine value.

Products don’t compete in a vacuum. They compete inside categories. And categories live on the Progression of Economic Value. That ladder you just saw explains why “better product” is not enough—and why this keeps getting mistaken for a product problem in the first place.

At the lower rungs of the ladder, value is defined by specs, features, and price.

A product can be extraordinary and still be trapped on the wrong rung.

That’s exactly what happened to Gateway.

The iPhone wasn’t positioned as a better phone, a faster PDA, or a more elegant BlackBerry. It wasn’t framed as a collection of features. It was framed as a transformation. “The internet in your pocket” wasn’t a hardware description. It was a new way of living.

The iPhone didn’t just perform tasks. It changed what people could do.

Product answered the question, “What can this thing do?”

Marketing answered the question, “What problem does this solve—and what changes after you own it?”

Those are category-level decisions. And category-level decisions determine where value lives.

Product creates capability.

Marketing creates meaning.

Product creates capability.

Marketing decided what the capability meant.

Capability without meaning gets commoditized. Meaning without capability is fraud. Apple had both. Gateway only had one.

That’s why this is not just a product problem.

If it were, marketing would always be downstream. It would always be a cost. It would always be a support function explaining decisions made elsewhere. And marketing would never earn its way onto the P&L.

But the moment you see that marketing decides what rung of the ladder a product competes on, everything flips. Marketing stops being promotion. Marketing becomes economic altitude control. And altitude is where pricing power, word of mouth, and profit live.

So no—this isn’t a product problem.

It’s the most expensive misunderstanding in modern business: confusing what you built with what the market believes it is.

Product creates the raw material. Marketing turns it into a category. And categories—not products—are what move you up the ladder.

Apple used marketing to move a product up the ladder.

Tesla goes one step further.

They use marketing to turn the ladder itself into a profit engine.

How Tesla Is Using The Rental Car Category As Profit-Positive Marketing

To see what this looks like when marketing itself becomes the product, we need to look at a category no one thought mattered.

Pirate Eddie is a Super of the rental car category. He holds President’s Circle status at both Avis and Hertz, earned the old-fashioned way—years of constant travel. During COVID, he single-handedly kept the Avis at the Kona airport alive by renting a car for nine months straight. Even as Uber rose, Eddie stuck with rentals. He’s an introvert. He prefers solitude to small talk, even in “quiet conversation mode.”

When new categories are launched, the Supers are always the first to move.

And Pirate Eddie is permanently walking away from legacy car rentals.

Tesla quietly entered the rental business and redesigned the category. Walk into a Tesla dealership and you can rent a Model 3 or Y for about sixty dollars a day. Ninety bucks gets you an S, X, or Cybertruck. And then come the Scooby Snacks: free Supercharging and free Full Self-Driving—seven times safer, with zero conversation required.

The kicker is this:

When Eddie picked up his Tesla rental, it recognized him. Seat position? Already set.

Spotify playlists? Loaded. Navigation history? Synced.

This wasn’t a rental.

This was an AI clone of his Tesla at home.

A Hertz rental car is a service. A Tesla rental car with unlimited charging and a software chauffeur that drives for you is a transformation.

Tesla isn’t trying to compete in the rental car category.

They are using the rental category as profit-positive marketing for its core business.

They’re using the rental category as profit-positive marketing for their core business.

Every rental becomes a paid test drive.

Every paid test drive becomes a vehicle sale.

Every extended experience becomes an upsell to higher-end models.

Every mile driven becomes a chance to convert skeptics to Full Self-Driving.

Every renter becomes a believer in the future Robotaxi and subscription mobility world Tesla is building.

Tesla Rentals are to legacy car rental what the iPhone was to the payphone—not a better version, but a replacement that reframes the entire experience.

Wall Street analysts have begged Tesla to advertise for years. Tesla refused. Because advertising is a legacy model—one where marketing is an expense.

Tesla’s asking a different question:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Category Pirates to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.